Help your patients strengthen their bones

iBoneAcademy is your source for scientific information on osteoporosis. Here you can access disease state education slides and video presentations to learn more about fractures and osteoporosis management.

Osteoporosis-related fractures can impact a patient's life. Help your patients strengthen their bones and reduce their risk for fractures.1-4

View the resources below to learn about the burden of osteoporosis, barriers to medication adherence, and how healthcare professionals can help with disease management.

In the second video of the Osteoporosis Clinical Insight Series, Dr. Watts discusses osteoporosis risk factors, screening for osteoporosis and fracture risk assessment.

#usa-785-81882Dr. Watts describes how osteoporosis is diagnosed and its subsequent evaluation in this third video in the Osteoporosis Clinical Insights Series.

#usa-785-81883In the final video of the Osteoporosis Clinical Insights Series, Dr. Watts takes a deep dive into DXA measurement of bone mineral density. Learn common pitfalls in DXA acquisition along with best practices to minimize such errors, what constitutes a good report, and the use of DXA-based equipment to identify vertebral fractures.

#usa-785-81885Medication adherence is essential for reducing the risk of fractures.4,5 Learn what keeps patients from taking their medications, understand their perspective, and learn how you can provide guidance.

Primary care practitioners have a key role in postfracture care. In this video, learn how they can help patients who have experienced a fracture avoid subsequent fractures.6

#usa-785-80938Osteoporosis is a common bone disease characterized by low bone mass and structural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to bone fragility and an increased risk of fractures.7 Watch this video to review the pathophysiology, consequences, management tips, and clinical guidelines for osteoporosis.

#usa-785-81419Several societies have released updated clinical practice guidelines for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Examine recent updates to the AACE, ENDO, and IOF-ESCEO guidelines.

#usa-785-81694Incidence of osteoporosis and osteoporosis related fractures are common and are projected to increase.8,9 Review the recent trends in the management of osteoporosis, including clinical guideline updates.

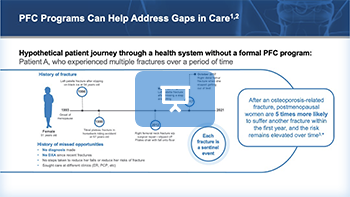

Post fracture care (PFC) programs are designed to systematically identify, diagnose, treat, and manage patients with osteoporosis, who are at high risk for secondary fractures because of compromised bone health.10 Learn about the gaps, benefits, implementation tips, and examples of a PFC program.

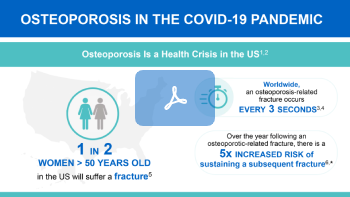

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed osteoporosis care for patients. Review recommended management strategies of osteoporosis during the pandemic.

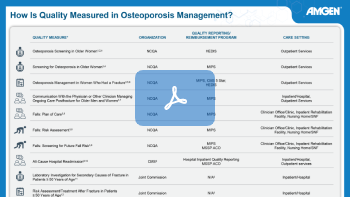

Quality measures in osteoporosis management have been established by several organizations and are important in holding care to higher standards. Learn about the different organizations and measurements available to uphold quality of care.

Evaluating patients for osteoporosis and their fracture risk requires consideration of several factors.4 Learn about tools and clinical risk factors to identify patients at high risk.

#usa-785-81934Patients may have questions and concerns about osteoporosis and treatment options. Explore communication strategies to help patients understand their diagnosis, and the benefits and risks of treatment.

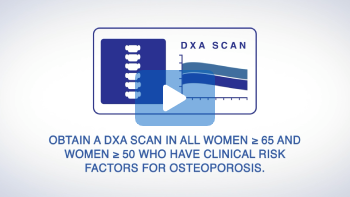

#usa-785-81935Diagnostic screening is critical for reducing the risk of fragility fractures.11 Learn about how the well-established DXA scan and new Biomechanical Computed Tomography (BCT) analysis can be utilized to address the gap in osteoporosis diagnosis.11

#usa-785-81752This transcript is provided for your convenience and is qualified by the full video in which the spoken content appears. Please review the full video along with the transcript.

In general, there is a lack of public awareness about osteoporosis.1

and a misconception that it is an unavoidable part of aging.2

Osteoporosis is more prevalent than you think. Approximately 200 million women worldwide are affected by osteoporosis.3

and worldwide 1 in 3 women over 50 years of age will suffer a fragility fracture.4

and fewer than 1 in 3 may be treated, even after experiencing a fragility fracture.5

References:

1. Harvey NC, McCloskey EV, Mitchell PJ, et al. Mind the

(treatment) gap: a global perspective on

current and future strategies for prevention of fragility

fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:1507-

1529.

2. Feldstein AC, Schneider J, Smith DH, et al. Harnessing

stakeholder perspectives to improve the

care of osteoporosis after a fracture. Osteoporos Int.

2008;19:1527-1540.

3. International Osteoporosis Foundation.

Epidemiology.

https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/health-professionals/aboutosteoporosis/

epidemiology. Accessed August 18, 2022.

4. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Epidemiology of

osteoporosis and fragility fractures.

https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/facts-statistics/epidemiology-of-osteoporosis-andfragility-

fractures. Accessed August 18, 2022.

5. Yusuf AA, Matlon TJ, Grauer A, et al. Utilization of

osteoporosis medication after a fragility

fracture among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Arch

Osteoporos. 2016;11:31.

This transcript is provided for your convenience and is qualified by the full video in which the spoken content appears. Please review the full video along with the transcript.

Fragility fractures at various sites are associated with significant clinical and personal burden.1

This may include: difficulty performing activities of daily living2,

admission to long-term care facilities,3

pain1 or complications from hospitalization,4

worry - which can impact relationships5, and

financial burden for patients6 and caregivers.7

Fragility fractures result in more hospitalizations than breast cancer, stroke, or myocardial infarction.8

A prior fragility fracture can substantially increase the relative risk of a future fracture.9

And the subsequent fracture can occur at the same or a different site from the initial fracture.9

References:

1. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician's Guide

to Prevention and Treatment of

Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381.

2. Fischer S, Kapinos KA, Mulcahy A, et al. Estimating the

long-term functional burden of osteoporosisrelated

fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:2843-2851.

3. Bentler SE, Liu L, Obrizan M, et al. The aftermath of hip

fracture: discharge placement, functional

status change, and mortality. Am J Epidemiol.

2009;170:1290-1299.

4. Inacio MC, Weiss JM, Miric A, et al. A community-based

hip fracture registry: population, methods,

and outcomes. Perm J. 2015;19:29-36.

5. Royal Osteoporosis Society. Life with Osteoporosis 2021:

the untold

story.

https://strwebprdmedia.blob.core.windows.net/media/1d5hdsg4/life-with-osteoporosis-

2021-public-report-final-1.pdf Accessed August 18, 2022.

6. Tarride JE, Hopkins RB, Leslie WD, et al. The burden of

illness of osteoporosis in Canada. Osteoporos

Int. 2012;23:2591-2600.

7. Kaffashian S, Raina P, Oremus M, et al. The burden of

osteoporotic fractures beyond acute care: the

Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos). Age

Ageing.

2011;40:602-607.

8. Singer A, Exuzides A, Spangler L, et al. Burden of

illness for osteoporotic fractures compared with

other serious diseases among postmenopausal women in the

United States. Mayo Clin Proc.

2015;90:53-62.

9. Gehlbach S, Saag KG, Adachi JD, et al. Previous fractures

at multiple sites increase the risk for

subsequent fractures: the Global Longitudinal Study of

Osteoporosis in Women. J Bone Miner Res.

2012;27:645-653.

10. Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, et al. Risk of subsequent

fracture after low-trauma fracture in men

and women. JAMA. 2007;297:387-394.

This transcript is provided for your convenience and is qualified by the full video in which the spoken content appears. Please review the full video along with the transcript.

Obtain a DXA scan in all women ≥ 65 and women older than 50 who have clinical risk factors for osteoporosis.1

Bone mineral density alone does not explain all fragility fracture risk.

Understanding clinical risk factors and BMD together improve fracture risk prediction in these patients.1 Determining a patient’s fracture risk requires consideration of several clinical risk factors, of which a history of prior fracture, older age, and low bone mineral density are most important, followed by other non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors.1

There are several methods you can use to identify women over age 50 at high risk for fracture that need treatment.1 Patients with a history of fracture at the hip or spine are at a high risk for future fracture.3

Women over age 50 with bone mineral density T-scores below –2.5 are considered osteoporotic and at high risk for future fracture.1

High-risk patients are those women with FRAX 10-year probability of hip fracture ≥ 3%, or 10-year probability of major osteoporotic fracture ≥ 20%.3

Fragility fractures at the proximal humerus, pelvis, and in some cases, wrist qualify patients as high risk for future fracture, when occurring in combination with low bone mineral density at the hip or spine.1,4 Please note that regional thresholds and criteria for treatment eligibility may vary.1

References:

1. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American

Association

Of Clinical

Endocrinologists/American College Of Endocrinology

Clinical

Practice Guidelines For The

Diagnosis And Treatment Of Postmenopausal

Osteoporosis-2020

Update. Endocr Pract.

2020;26(suppl 1):1-46.

2. Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, et al. Bone mineral

density

thresholds for pharmacological

intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med.

2004;164:1108-1112.

3. Shoback D, Rosen CJ, Black DM, et al. Pharmacological

Management of Osteoporosis in

Postmenopausal Women: An Endocrine Society Guideline

Update. J

Clin Endocrinol Metab.

2020;105:dgaa048.

4. Siris ES, Adler R, Bilezikian J, et al. The clinical

diagnosis of osteoporosis: a position statement

from the National Bone Health Alliance Working Group. Osteoporos

Int. 2014;25:1439-1443.

This transcript is provided for your convenience and is qualified by the full video in which the spoken content appears. Please review the full video along with the transcript.

Doctor: It’s not just a wrist fracture … your bone mineral density test at your hip indicated that you have osteoporosis because your T-score is below minus 2.5.1 Having this first fracture increases your risk for having another fracture in the future which could be at a different site.2 All of your other tests were normal. I recommend you start treatment for your osteoporosis.

Patient thought bubble 1 (read in a whispering voice by patient): Osteoporosis? I don’t know, that fall was an accident. I just need to focus on healing my wrist and then I’ll be more careful.3 Patient comment bubble 1 (read in a regular voice by patient): I have seen media reports about the side effects of those treatments. I need to do more research … I don’t want to start treatment just yet.1

Understand, acknowledge, and discuss your patient's concerns, but also ensure they understand that osteoporosis is a real disease that weakens their bones and makes them more likely to break.1,4

While the fears of treatment side effects are real, ensure your patient understands that osteoporosis is a chronic disease, and for many, the risks of the disease outweigh the risks of treatment.5

When discussing treatment options and the potential for adverse events, consider presenting statistics in an understandable way by using absolute numbers and visual aids.1

Encourage your patient to ask questions which promotes shared decision making and helps to identify what's most important to the patient and barriers to management.1

References:

1. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/ American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2020 Update. Endocr Pract. 2020;26:1-46.This transcript is provided for your convenience and is qualified by the full video in which the spoken content appears. Please review the full video along with the transcript.

Osteoporosis is a very common bone disease, particularly among female patients after menopause.1

Today I would like to review with you the physiology, consequences of, and some tips on osteoporosis management.

I will also include updates to the clinical practice guidelines that come from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE).2

My name is Amanda McKee. I am a family nurse practitioner. I'm also an orthopedic nurse practitioner and a certified clinical densitometrist.

This disease awareness program is presented on Amgen's behalf and has been reviewed with consistent with Amgen's internal review policy.

Speaker disclosures…

Let’s first set the stage so that we have a common lexicon.

The World Health Organization has defined osteoporosis as a disease characterized by low bone mass and structural deterioration of bone tissue, and these two conditions lead to bone fragility as well as an increased risk of fractures.3

And a fracture is the clinical end result that we want to prevent, because as you may be well aware of, a fracture can be debilitating to patients.4

Before we can discuss the pathophysiology of osteoporosis, we need some of the basics of bone anatomy and physiology.

At the center here is an illustration of typical long bone – such as a femur in the thigh, or the radius in the forearm. There are 2 major components – the trabecular bone (which is the inside portion) and the cortical bone (which is on the outside).5

The trabecular bone is a honeycomb-like network of delicate, interconnected plates that looks like a sponge.5,6

Although it seems to occupy a lot of space, it represents only 20% of total bone mass.6

The trabecular bone acts as major reserve for calcium and phosphate in the body, and provides a large surface area for mineral exchange.7,1

The orientation of the trabecular plates also allows for maximal strength without much of the bulk, similar to how we design buildings and bridges.1

Finally, the trabecular bone is the major site for bone remodeling, which we will discuss in more detail later, and has a higher turnover rate.2,7

Next, the cortical bone is quite different. It is dense, it defines the shape of the bone, and it accounts for most of the skeletal mass.1

Functionally, the cortical bone provides biomechanical strength, it serves as attachment sites for tendons and muscles that are associated with movement, and it protects organs that the bone surrounds such as the bone marrow and the brain. 1,7,8

The turnover rate for cortical bone is slow, at 2%–3% per year, which is sufficient for maintaining the biomechanical strength of the bone.8

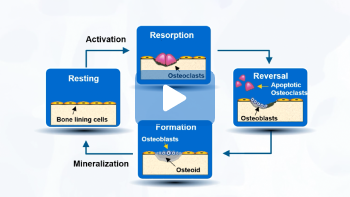

What is bone remodeling, and why do we need it? Bone remodeling is a normal, physiological, and continuous process that is needed to maintain a healthy skeleton.1

Remodeling repairs damage to the skeleton that can result from stresses. It

prevents accumulation of old, brittle bone.

And it is important for the function of the skeleton as the storage for calcium and phosphorous. In

fact, most of the adult skeleton is replaced about every 10 years.1

Bone remodeling follows a specific sequence of events. Let’s start by orienting ourselves to the Resting stage of the cycle. Here, the lining cells occupy the surface of the bone.9

[Click] It has been suggested that certain bone cells can sense bone stress that is caused by mechanical loading or microdamage to the bone, and activates the remodeling cycle. 7,10

During the Resorption phase, cells called osteoclasts are recruited to the bone. These cells secrete various enzymes and acids to destroy the old bone matrix.9,10

[Click] The next phase is called Reversal. During this phase, a new group of cells called osteoblasts to the site where the osteoclasts have vacated.10

[Click] Next is the Formation phase. Now, the osteoblasts are responsible to lay down new bone matrix –

this organic component is called osteoid – to fill up the hole.7,9

As a final step, the osteoid undergoes a process called mineralization, and completes the remodeling process for the bone.10

The entire process itself takes approximately 3–6 months.9

In normal bone remodeling, bone formation and bone resorption is balanced, so there are no major net changes in bone mass or mechanical strength after each cycle.7

However, In osteoporosis, the bone remodeling process is out of balance because bone resorption exceeds bone formation. There can be a variety of reasons that can lead to this remodeling the slowdown in bone formation, or an acceleration of bone resorption, or both.1

One important cause of osteoporosis is a decrease in the production of sex hormones, both estrogen and testosterone, which leads to an increase in osteoclast activity, an acceleration in bone resorption, a lower bone mineral density, and eventually increasing the risk of fracture.1,11

In postmenopausal women, there is an increase in bone resorption that’s primarily associated with a deficiency in estrogen. Postmenopausal women are therefore at high risk for developing osteoporosis.11-13

Let’s go just one level deeper to explain the relationship between a decline in estrogen level and excessive bone remodeling. There are many participants in the bone remodeling process.

[Click] But for the purpose of this discussion, we are going to focus on the relationship of these five players.

[Click] First, the discovery of the essential role of RANK ligand pathway which was a major milestone in the understanding of bone regulation and bone pathology, including postmenopausal osteoporosis.7

RANK ligand is a cytokine that can be bind that can bind to its receptors on osteoclasts. This increases the number and activity of osteoclasts. Therefore, more RANK ligand leads to more bone resorption.7,11

[Click] It turns out that there is another receptor for RANK ligand, called OPG. OPG is a soluble decoy receptor that is derived from osteoblasts, and can bind to RANK ligand, and as a result antagonizing bone resorption. 7,10,11,14

[Click] Estrogen exerts its bone-sparing effects by targeting this system, but indirectly. It turns out that estrogen has a profound impact on osteoblasts, the bone-forming cells. Estrogen signals the osteoblasts to increase production of OPG, resulting in a reduction in RANK ligand and bone resorption.7,11

In postmenopausal women, the lack of estrogen leads to an increase in RANK ligand, and its ability to stimulate bone resorption, increasing the risk of this population in developing osteoporosis and fracture.7

Let’s take a closer look at the change in bone mass throughout the life span. Bone accumulates rapidly in childhood and grows rapidly during puberty. Peak bone mass is reached by age 30, and then slowly decreases as we get older. This is observed in both males and females.15

There are a couple of notable differences between genders. In general, bone mass in men is higher than women. After 40 years old, bone mass in men gradually declines.15

In contrast, females typically accumulate less bone mass than males, and rapidly lose bone during menopause.15

And according to National Osteoporosis Foundation, as much as 20% of their bone mass can be lost during the first 5 to 7 years following the start of menopause.16

So, many women in their 50’s may already have low bone mass, making them more susceptible to osteoporosis later in life.15

The image in the top panel shows what normal bone looks like.

As we age, bone formation tends to decrease, usually failing to keep up with the rate of bone resorption. The imbalance between bone resorption and bone formation leads to a loss in bone mass, and the development of structural abnormalities.1

This result is how we are characterizing osteoporosis:

Disruption to bone architecture17

Compromised bone strength17

And an increased risk of fracture.4

Now that we have a high-level overview of bone physiology and osteoporosis pathology, let’s turn our attention to the burden of osteoporosis.

One study estimated the prevalence of osteoporotic fractures to be over 2 million based on data from 2005. And more alarming is that the projection for the year 2025 –is only 5 years away – is expected to be about 3 million. This represents a 48% increase in osteoporotic fractures in just over 20 years.13

Furthermore, approximately 50% of women 50 years and older in the United States are expected to experience an osteoporotic fracture some time during their remaining years.18

While breast cancer garners significant attention when we talk about diseases in women in the United States, you may be surprised to know that the incidence of osteoporosis-related fractures is actually a lot higher than breast cancer diagnosis.19

In 2006 among women of all ages – not just the ones over 50 years old –number of new cases of breast cancer was just over 200,000 a year.19

In contrast, in 2005 just hip fractures alone accounted for 200,000 cases, not to mention the fractures of the spine, the wrist, and other sites. Overall, the annual incidence of osteoporotic-related fracture among women of all ages was 1.4 million, or 6-fold higher than breast cancer diagnosis.19

Osteoporosis is a "silent" disease, meaning that the first sign of the disease is often a fracture.4

Fractures occurring at certain key sites in women over the age of 50 should be a signal to healthcare professionals to evaluate osteoporosis further.4,20

Major sites of osteoporosis-related fractures are highlighted here, with vertebral fractures being the most common, followed by fractures of the wrist, and then fractures of the hip.4,18,19

Of note, the majority of vertebral fractures are initially relatively asymptomatic, so it is not surprising that it remains undetected in approximately two-thirds of the cases.3,21

Although wrist fractures are typically less debilitating, but it can interfere with some activities of daily living.4

It should not be surprising that a hip fracture cause the most debilitating osteoporosis complications there is.4,22

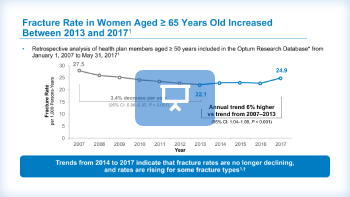

The establishment of screening and treatment guidelines for osteoporosis have facilitated a decline in fracture rates between 2007 and 2013.23

Specifically among women 65 years and older, the fracture rate dropped from 27.5 fractures for every 1,000 person-years, down to about 22. This represents a significant decrease of 3.4% per year.23

However, in more recent years, the fracture rate has reversed course and has been climbing up again.23

The data points shown in blue on this graph show a relative plateau since 2013, then an increase in fracture rates among women over the age of 65 in 2017.23

Many factors may have played a role in contributing to the increasing fracture rates.23,24

Since 2007, Medicare reimbursement for bone density screening was cut far below the actual cost of performing a DXA – or dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry – scan. As a result, these services were less likely be offered by rheumatologists, physicians in solo practices, and practices where access to fewer than three DXA scanners.24

Osteoporosis-related fractures can have a negative impact on the patient. Let’s take a look at some of the major issues.

An osteoporosis-related fracture may prevent a person from caring for herself; for this reason, she may require admission to a nursing home or a long-term care facility.25

Next, Costs due to osteoporosis-related fracture can create a heavy financial burden for the affected person and their caregivers.26,29

The patient may not be able to do some of the regular activities of daily living because of the fracture.4,25,30

Then they may Worry about falls, the possibility of future fractures, and the potential need for nursing home care is sometimes experienced by a person with an osteoporosis-related fracture.27,31

And finally, complications such as chronic pain and other complications may occur as well. 4,32

Once a patient experiences a fracture, the risk of having a subsequent fracture goes up.33

A study published in JAMA followed a cohort of ambulatory patients over a 16-year period. These patients lived in community and not in a nursing home.33

Among elderly women who had a prior fracture, researchers found the risk of an initial fracture went up with age.33 In addition, the risk for a subsequent fracture went up by 1.6 to 2.4 times.33

In fact, the risk of a subsequent fracture amongst women aged 60–69 years old who had a prior fracture (36%), was higher than the risk of an initial fracture amongst women aged 70–79 years old (at 27%).33

The same goes with those in the age of 70–79 who had a prior fracture. Their risk for a subsequent fracture (63%) was higher than the risk of an initial fracture in those who were 80 years of age or older (at 50%).33

This data underscores the fact that the increased risk of a subsequent fracture persists for up to 10 years depending on age and sex.33

I always like to say that a fracture begets a fracture.20

In fact, when we examine the period following an osteoporosis-related fracture more closely, it becomes more clear that the highest risk of a re-fracture is within the first year after the initial fracture.34

This can be illustrated using data from a population-based study over 4,100 postmenopausal women.34

In this study, fractures included hip fractures, major fractures (which include clinical vertebral fractures, forearm, and humerus), and minor fractures (all others), as classified by the World Health Organization.34

The relative risk of a subsequent fracture is 5 times greater in the first year after a fracture compared with the risk of a first fracture. In fact, one of every four subsequent fractures happen within the first year after the initial fracture. This supports early action in prevention of a subsequent fracture.34

Again, remember that a fracture begets a fracture.20

Although various types of fractures can occur in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, vertebral fractures are independent risk for future fractures.4,35One of every four women who experience a vertebral fracture will have a second fracture within 2 years.35

In fact, the risk of the second fracture being another vertebral fracture is 7.3 times higher among women aged 55 years or older with a history of a vertebral fracture.36

However, most vertebral fractures go undiagnosed at the time that they occur due to lack of symptoms. 21,37,38

Because of increased risk of second fracture, it is most important to identify those postmenopausal women who have a vertebral fracture.39 Candidates for assessment may have one or more of the following characteristics:

Significant height reduction, either historically with a difference of 1.5 inches or more between the peak height at age 20, or prospectively with a difference of 0.8 inches or more between a previously documented height measurement compared to the current height4,39

They may also have Postural changes including stooping or progressive spinal curvature1,39 Or worsening or unexplained back pain39

To detect vertebral fractures, vertebral fracture assessments – also known as VFA – imaging, or lateral x- ray are often used.37,39

Among all the osteoporotic fractures, the worst consequences can occur with hip fractures.22

It is not surprising then like those with vertebral fractures are increased risk of a subsequent vertebral fracture, those with hip fractures are at increased risk of future hip fractures.36

In fact, women who have hip fracture have a 3.5-fold greater risk of a second hip fracture.36

[Click] In addition, the probability of needing care in long-term nursing facility is increased 4-fold after a hip fracture.26

[Click] Despite these increased risks, a study found that only ~11% to 13% of patients receive pharmacological therapy for osteoporosis within 3 months of the hip fracture.22

How good does BMD by itself predict the risk of fracture?I would like to share with you results of a large observational study done in the United States, which involved approximately 150,000 women who were white, postmenopausal, over 50 years of age, and were NOT diagnosed with osteoporosis. A baseline BMD T-score was measured, and new fractures over the following 12 months were documented.40

The x-axis is the BMD T-score, with the best score to the left and the worst to the right.

The green dotted curve shows distribution of BMD T-scores, which approximates a normal distribution.2,40

The blue columns are the fracture rates. There was a strong continuous relationship between lower BMD T-scores and a higher fracture rate, which could not be too surprising. Notice also that fractures did occur in those women who did not have a BMD T-score in the osteoporotic range.40

It is crucial to recognize that these fractures are associated with skeletal fragility even though they do not have a T-score in osteoporosis range.40

[Click] The real insight comes when we consider these two findings together. The red bars here represent the absolute number of women with new fractures based on BMD T-scores.40

A large number of osteoporotic-related fractures occurred in patients with low bone mass, because of the large number of patients with bone mass in this range.4

Take a look at the red bars inside the gray box. These were women who experienced a new fracture, despite having a BMD T-score of better than a –2.5. And this represents over 80% of women with a new fracture.40

What this study shows is BMD T-scores alone is not a very good predictor of future risk of having a fracture.40

If a low bone density alone is not a very good predictor of future risk of fracture, then what else is there?

It turns out there are a whole host of risk factors that have been associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis-related fractures.4

These range from prior fracture, age, to parental history of hip fracture, low body mass index, immobilization, long-term glucocorticoid use, alcohol use, smoking, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and whether there is a high risk of falling. This is just a abbreviated short list.2,4

In general, there are more risk factors that are present, the higher risk there is for a future of fracture.4

One of these risk factors – having a prior fracture – is particularly important predictor of future fracture risk.2

As we have discussed before, postmenopausal women who had an osteoporotic-related fracture were found to be 5 times more likely to suffer another fracture within the first year following.34

And in fact, as we will review later, prior fracture is being emphasized in the latest guideline in diagnosing osteoporosis.2

The first step in managing osteoporosis is to properly establish a diagnosis. It is important to note that the guidelines point out osteoporosis can be diagnosed with a low BMD, or a history of fracture, or some other combinations.2

This year the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) updated its guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis.2

According to these guidelines, a diagnosis of osteoporosis can be made if ANY ONE of the following 4 criteria are met:2

The first is having a BMD T-score of –2.5 or worse in any of the major sites. This is a group of patients we traditionally think of when we think about osteoporosis. However, diagnosis can also be made with the following criteria as well:

A low-trauma fracture of the hip, the spine, regardless of BMD score, OR

A T-score T-score between –1 and –2.5, PLUS a fragility fracture of proximal humerus, pelvis, or distal forearm, OR

a T-score of –1 to –2.5, PLUS a high FRAX® fracture probability. If a trabecular bone score-adjusted FRAX® score is available, use that instead.

Once a diagnosis of osteoporosis is made, the diagnosis persists for the rest of the patient’s life. And this is true even if aggressive management results in an improvement of the BMD T-score to be better than – 2.5.2

There are a number of reasons for this:

First, we know that osteoporosis is a chronic, progressive silent disease, much like hypertension or diabetes.41

The goal of management is to prevent fractures, but no treatment can eliminate the risk of fracture.2

There is also no consensus of what an acceptable level of fracture risk should be, whether based on BMD measurement or monitoring of FRAX® scores.2

Therefore, management of osteoporosis needs to be long-term, once a diagnosis is made.2

For example, AACE guidelines endorse lifelong physical activities for osteoporosis prevention.2

So how do we identify patients who may be at high risk of osteoporosis fractures?

First, If a patient is 50 or older, and is postmenopausal, evaluate for risk of osteoporosis.2

We can look for signs or symptoms to see if further testing is needed. These further tests may include BMD measurements, or vertebral imaging to detect future fracture.2

For example, does the patient have unexplained back pain? 2

Or Does the patient have kyphosis – which is an abnormal spinal curvature?2

How about an unexplained loss of height? Ideally, this is measured once a year using a wall-mounted stadiometer.2,4

This loss of height can be defined two different ways. A historical height loss difference between the patient’s current height versus peak height age 20. A loss of 1.5 inches, or 4 cm, is associated with a new vertebral fracture.2,4

Another definition is called prospective height loss, which is the height which is the difference between the patient’s current height and a previously recorded height. A prospective height loss of 0.8 inches or more than 2 cm is also associated with a new vertebral fracture.2,4

[Click] You should ask the patient questions related to possible osteoporosis risk factors.4

For example, is there a parental history of hip fracture?

Is the patient using any medication that may be associated with bone loss?

Once a patient has been found to be at high risk for fracture and osteoporosis, a central DXA scan is usually ordered to measure the bone density, usually of the hip and the spine.2,42

Only results from a central DXA can be used to establish a diagnosis of osteoporosis, because peripheral tests such as the peripheral dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (pDXA), quantitative ultrasound (QUS), and peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) are useful for screening. Moreover, results of a peripheral DXA cannot be compared to that of a central test.42

DXA usually takes about 10 minutes to perform.16,42 And

it is used to obtain a patient’s BMD T-score.42

In addition to its role in diagnosis, DXA is also used to monitor treatment for osteoporosis.2

The AACE 2020 guidelines recommend an axial DXA scan every 1 to 2 years until the findings are stable.2,42

Medicare Part B covers DXA scan once every 24 months to monitor osteoporosis treatment if certain conditions are met.43

Ideally, repeat DXA scans should be done at the same location, using the same equipment for the most accurate comparison of results.42

As I mentioned earlier, the T-score obtained with a DXA scan can be used to determine fracture risk and diagnose osteoporosis.2

The T-score is defined as standard deviation of an individual’s bone mineral density (BMD) from the mean value for young normal white women.2

As the T-score decreases, the BMD decreases. And as BMD decreases, the risk of fracture increases.2

This slide shows a range of T-scores and their relationship to bone health.

The left end of this illustration shows T-scores ranging from −1.0 and 0, which indicate normal bone density. At the right end of the figure are T-scores of −2.5 or lower; as I pointed out earlier, a T-score that is less than or equal to −2.5 is sufficient for diagnosis of osteoporosis. Between the T-scores for normal bone and osteoporotic bone are the T-scores indicating osteopenia. Keep in mind that osteoporosis can be diagnosed if the T-score is between −2.5 and −1.0 and the patient has had a prior fragility fracture of the proximal humerus, pelvis and/or distal forearm.2,4

It is possible that a T-score may increase and surpass −2.5 with therapy; regardless, osteoporosis persists despite this improvement.2

A patient’s 10-year risk of fracture can be assessed with tools such as a FRAX®, which is an algorithm designed by the World Health Organization for use in primary care.44

The risk is calculated based on clinical factors can be easily collected, as summarized on the left side of the slide.44

Data regarding the risk factors can be entered directly into the FRAX® calculator online, as depicted in the middle portion of this slide.

Once the clinical data has been entered, the FRAX® calculator will generate a 10-year probability of a hip fracture and a 10-year probability of a major osteoporosis-related fracture.44

The right side of this slide shows how the output should be analyzed, based on the thresholds at which osteoporosis treatment is expected to be cost-effective.45

The intervention threshold for hip fracture risk is 3% or greater. 45

Likewise, the intervention threshold for a major osteoporotic fracture is 20% or greater.45

Note that we refer to a “major” osteoporotic fracture as a fracture of the hip, the spine, the humerus, or the wrist.44

Although primary care providers often diagnose and manage osteoporosis, a referral to endocrinologist or other osteoporosis specialist may be considered if the patient has one or more of the following characteristics shown on this slide:2

A normal BMD and a fracture due to a nontraumatic event. A normal BMD is defined as a T-score −1.0 or above, however, patients with low bone mass or osteopenia with a T-score between −1.0 and −2.5 with a fragility fracture are also increased risk for future fracture events.

A recurrent fracture or ongoing bone loss despite therapy for osteoporosis and no other apparent cause of bone loss. Also, Secondary conditions, such as hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, hypercalciuria, or increased prolactin.

Conditions that may complicate treatment, such as renal impairment, malabsorption, or hyperparathyroidism.

Also, Severe osteoporosis or osteoporosis with unusual features, such as young age, a low phosphorus, abnormal alkaline phosphatase, or abnormal lab results.

Also, Unexplainable artifacts on DXA scans. Or

Osteoporosis-related fracture.

An osteoporosis-related fracture is one that occurs in a patient with osteoporosis who experiences minimal trauma, such as a fall from standing height or less.1

The risk of fracture stems not only from bones becoming more fragile, but also from the increased risk of falls due to loss of muscle strength and function with age. After the age of 30, approximately 5% of muscle mass is lost with every decade of life, and this rate only accelerates beyond age 65. It is not surprising then that one in every four women age 50 or older and one in two women age 85 or older, falling annually.1

Falls contribute to 25% of the clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures, whereas the majority of clinically diagnosed fractures result from excess stresses on the spine caused just by everyday activities.1

If an adult older than 50 years has a fracture at any major skeletal site, consider that a warning sign that this patient may have low bone density or osteoporosis. Further evaluation of the patient is required.4

Today, osteoporosis is managed by lifestyle modifications as well as pharmaceutical therapy.16,46

Lifestyle modifications include getting sufficient calcium and vitamin D, engaging in exercise to improve strength and balance, avoiding tobacco, limiting alcohol use, and taking steps to prevent falls, which can cause fracture. 2,16,47

Calcium supplements of 1,200 mg/day for women age 50 and older and vitamin D is recommended.2

Weight-bearing exercises such as walking for 30–40 minutes and posture exercises for a few minutes should be done regularly (which is 3–4 days per week) muscle strengthening exercises such as lifting weights are important for building and maintaining bone density. 2,48

Also, cigarette smoking is known to be detrimental to bone health, although it is not clear whether it is due to enhanced metabolism of estrogen or direct effects on bone metabolism.2

Since excessive alcohol intake is also associated with increased risk of fracture, for postmenopausal women at high risk for osteoporosis consumption of alcohol should be limited to 2 drinks daily, with each drink being equivalent to 120 mL of wine, or 30 mL of liquor, or 260 mL of beer.2

Fall prevention strategies include optimizing drugs that affect the central nervous system or blood pressure, minimizing environmental factors such as poor lighting or loose rugs, and improving strength and balance.1,2

There are also a variety of pharmaceutical therapies that are target the different pathophysiological pathways of osteoporosis.2

In this Expert Theater, we have discussed three areas about postmenopausal osteoporosis and osteoporotic-related fractures.

The reduction estrogen after menopause upsets the balance in bone remodeling through its effect on the RANK ligand pathway, resulting in excessive bone resorption and increased risk of fracture.7

Clinically, a fracture can result in significant disability and loss of independence for the patient.4

In addition, once a patient has a fracture, she is at a much higher risk of having another one, especially in the next 1–2 years following.34

Therefore, it is important for us to identify patients who are at risk for osteoporosis as early as possible.

For every patient over the age of 50, we can routinely evaluate by looking for unexplained back pain or height loss, and ask about other risk factors.2,4

If you know that the patient recently has a fracture at any of the major skeletal sites, it is a trigger for us to investigate further.4

We also have tools – such as a DXA scan, vertebral imaging, and FRAX® risk assessment – that can further guide our actions with those patients we consider to be at high-risk, whether to establish a diagnosis, or refer to a specialist. 2,4,42,44

Finally, we need to manage osteoporosis like a chronic,

progressive disease with a long-term goal of

reducing the risk of fractures risk. Once a diagnosis of

osteoporosis is made, the patient will need to be

monitored and treated for the long haul.2,4

I hope this discussion has provided you with some

insight

and practical guidance into the epidemiology

and physiology of osteoporosis and osteoporotic

fracture in

women after menopause, as well as some

practical guidance in the diagnosis and management. If you have any question whatsoever, please contact

Amgen

Medical Information. And I would like to thank you for joining me throughout

this

presentation. References:

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. Bone

health

and osteoporosis: a report of the

surgeon general. 2004.

2. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American

Association of Clinical

Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology

clinical

practice guidelines for the diagnosis

and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2020

update.

Endocr Pract. 2020;26(suppl1):1-

46.

3. WHO Study Group. Assessment of fracture risk and

its

application to screening for

postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study

Group.

World Health Organ Tech Rep

Ser. 1994;843:1-129.

4. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician's

guide

to prevention and treatment of

osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381.

5. Willems NMBK, Langenbach GEJ, Everts V, Zentner

A.

The

microstructural and biomechanical

development of the condylar bone: a review. Eur J

Orthod.

2014;36:479-485.

6. Dempster DW. Primer on the Metabolic Bone

Diseases

and

Disorders of Mineral Metabolism.

6th ed. 2006:7-11.

7. Feng X, McDonald JM. Disorders of bone

remodeling.

Annu

Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2011;6:121-

145.

8. Clarke B. Normal bone anatomy and physiology.

Clin J

Am

Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(suppl 3):S131-

S139.

9. Baron R. General principles of bone biology. In:

Primer

on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and

Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 5th ed. 2003:1-8.

10. Baron R, Hesse E. Update on bone anabolics in

osteoporosis treatment: rationale, current status,

and perspectives. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

2012;97:311-325.

11. Michael H, Harkonen PL, Vaananen HK, Hentunen

TA.

Estrogen and testosterone use different

cellular pathways to inhibit osteoclastogenesis and

bone

resorption. J Bone Miner Res.

2005;20:2224-2232.

12. Raisz LG. Pathogenesis of osteoporosis:

concepts,

conflicts, and prospects. J Clin Invest.

2005;115:3318-3325.

13. National Osteoporosis Foundation. What women

need to

know. Available at:

www.nof.org/preventing-fractures/general-facts/what-women-need-to-know/.

Accessed

October 5, 2020 .

14. Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast

differentiation and activation. Nature.

2003;423:337-342.

15. Hodges JK, Cao S, Cladis DP, Weaver CM. Lactose

intolerance and bone health: the challenge of

ensuring adequate calcium intake. Nutrients.

2019;11:718.

16. National Osteoporosis Foundation. General facts.

Available at: www.nof.org/preventingfractures/

general-facts/. Accessed September 21, 2020.

17. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis

Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy.

Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy.

JAMA.

2001;285:785-795.

18. Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB,

King

A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic

burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the

United

States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res.

2007;22:465-475.

19. Watts N, Bilezikian JP, Camacho PM, et al.

American

Association of Clinical Endocrinologists

medical guidelines for clinical practice for the

diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal

osteoporosis. Endocr Pract. 2010;16(suppl 3):1-37.

20. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Capture

the

fracture. Available at:

www.capturethefracture.org/about. Accessed September

21,

2020.

21. Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ

3rd .

Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral

fractures: a population-based study in Rochester,

Minnesota, 1985-1989. J Bone Miner Res.

1992;7:221-227.

22. Kim SC, Kim MS, Sanfelix-Cimeno G, et al. Use of

osteoporosis medications after hospitalization

for hip fracture: a cross-national study. Am J Med.

2015:128:519-526.

23. Lewiecki EM, Chastek B, Sundquist K, et al.

Osteoporotic fracture trends in a population of US

managed care enrollees from 2007 to 2017. Osteoporos

Int. 2020;31:1299-1304.

24. Hayes BL, Curtis JR, Laster A, et al.

Osteoporosis

care in the United States after declines in

reimbursements for DXA. J Clin Densitom.

2010;13:352-360.

25. Bentler SE, Liu L, Obrizan M, et al. The

aftermath

of hip fracture: discharge placement,

functional status change, and mortality. Am J

Epidemiol.

2009;170:1290-1299.

26. Tajeu GS, Delzell E, Smith W, et al. Death,

debility, and destitution following hip fracture. J

Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:346-353.

27. National Osteoporosis Society. Life with

Osteoporosis. October 2014. Available at:

https://theros.org.uk/media/1859/life-with-osteoporosis.pdf.

Accessed September 21, 2020.

28. Tarride J-E, Hopkins RB, Leslie WD, et al. The

burden of illness of osteoporosis in Canada.

Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:2591-2600.

29. Kaffashian S, Raina P, Oremus M, et al. The

burden

of osteoporotic fractures beyond acute care:

the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos).

Age

Ageing. 2011;40:602-607.

30. Fischer S, Kapinos KA, Mulcahy A, Pinto L,

Hayden O,

Barron R. Estimating the long-term

functional burden of osteoporosis-related fractures.

Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:2843-2851.

31. Vass CD, Sahota O, Angelova T. Fear of falling

after

fragility fracture–a prevalence study. Age

Ageing. 2014;43:i29.

32. Inacio MCS, Weiss JM, Miric A, Hunt JJ, Zohman

GL,

Paxton EW. A community-based hip

fracture registry: population, methods, and

outcomes.

Perm J. 2015;19:29-36.

33. Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA. Risk

of

subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture

in men and women. JAMA. 2007;297:387-394.

34. van Geel TACM, van Helden S, Geusens PP, Winkens

B,

Dinant G-J. Clinical subsequent fractures

cluster in time after first fractures. Ann Rheum

Dis.

2009;68:99-102.

35. Roux C, Fechtenbaum J, Kolta S, Briot K, Girard

M.

Mild prevalent and incident vertebral

fractures are risk factors for new fractures.

Osteoporos

Int. 2007;18:1617-1624.

36. Gehlbach S, Saag KG, Adachi JD, et al. Previous

fractures at multiple sites increase the risk for

subsequent fractures: the Global Longitudinal Study

of

Osteoporosis in Women. J Bone Miner

Res. 2012;27:645-653.

37. Gehlbach SH, Bigelow C, Heimisdottir M, May S,

Walker M, Kirkwood JR. Recognition of

vertebral fracture in a clinical setting. Osteoporos

Int. 2000;11;577-582.

38. Nevitt MC, Ettinger B, Black DM, et al. The

association of radiographically detected vertebral

fractures with back pain and function: a prospective

study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:793-800.

39. The International Society for Clinical

Densitometry.

VFA patient information. Available at:

www.iscd.org/patient-information/vfa/. Accessed

September 21, 2020.

40. Siris E, Cheng YT, Abbott TA, et al. Bone

mineral

density thresholds for pharmacological

intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med.

2004;164:1108-1112.

41. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician's

guide

to prevention and treatment of

osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis

Foundation; 2014.

42. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Bone density.

Available at:

www.nof.org/patients/diagnosisinformation/

bone-density-examtesting/. Accessed September 21,

2020.

43. Medicare. Bone mass measurements. Available at:

www.medicare.gov/coverage/bone-massmeasurements.

Accessed September 21, 2020.

44. Kanis JA, Hans D, Cooper C, et al.

Interpretation

and use of FRAX in clinical practice. Osteoporos

Int. 2011;22:2395-2411.

45. Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, Dawson-Hughes B,

Melton LJ 3rd, McCloskey EV. The effects of a

FRAX revision for the USA. Osteoporos Int.

2010;21:35-40.

46. National Institute of Health. Osteoporosis

overview.

Available at:

https://www.bones.nih.gov/health-info/bone/osteoporosis/overview.

Accessed October 5,

2020.

47. Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad

MH,

Shoback D. Pharmacological

management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women:

an

Endocrine Society clinical practice

guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

2019;104:1595-1622.

48. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis

exercise for strong bones. Available at:

https://www.nof.org/patients/treatment/exercisesafe

movement/osteoporosis-exercise-forstrong-

bones/. Accessed November 1, 2020.

This transcript is provided for your convenience and is qualified by the full video in which the spoken content appears. Please review the full video along with the transcript.

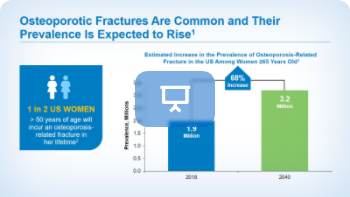

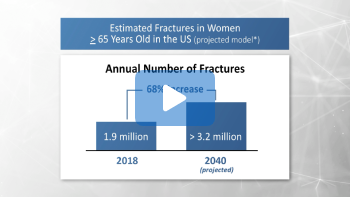

The annual number of fractures in women at least 65 years old in the US is projected to increase in the next two decades.1

Diagnostic screening is critical for reducing the risk of fragility fractures.2

Bone Mineral Density, as measured by a DXA scan, is the clinical standard for diagnosing osteoporosis.3

Yet, while DXA testing is well established, fewer than 10% of women and 2% of men in the eligible Medicare population were tested each year.4,5

A Medicare-reimbursed bone test called Biomechanical Computed Tomography analysis, or BCT, is now available.2

Because it can utilize most CT scans taken for any medical indication that capture the hip or spine, BCT can provide a fracture risk assessment without the need for an extra patient procedure or additional radiation exposure.2

Let’s consider a hypothetical clinical case of a 70-year-old woman that presents to the ER with unexplained stomach pain and undergoes an exploratory pelvic-abdominal CT.

In reviewing her medical history, her physician incidentally notes that she is at increased risk of osteoporosis due to age,3 but has not received an osteoporosis test in recent years. So he orders a BCT test and the patient’s pelvic abdominal CT scan is sent from the hospital to a BCT testing facility.

There, a biomechanically-accurate 3D model of the patient’s hip or spine is created from the scan data. 2

The model is then subjected to a virtual stress test that simulates a sideways fall for the hip or a compressive overload for the spine, with the regions of tissue failure colored red thus assessing the bone’s breaking strength and fracture risk.2

The results of the BCT test are summarized in a report that can include hip BMD T-scores suitable for use with FRAX®. 2

Based on both the BMD and bone strength measurements BCT can be used to diagnose osteoporosis and provides an overall fracture risk classification of: high risk, increased risk, or not-increased risk.2

The BCT medical report is then returned to the ordering physician who uses it to assemble a patient care plan.

As a newer clinical test, BCT is not yet widely adopted. And while BCT can be applied to most clinical CT scans that contain the proximal femur or lower spine, analysis may not be possible due to factors such as poor image quality or the presence of metal implants.2

In summary, the BCT clinical test can provide mechanistic insight about bone strength and fracture risk while helping to address the osteoporosis diagnosis gap.2,6

References:

1. Lewiecki EM, et al. JBMR Plus. 2019;3:e10192.

2. Keaveny TM, et al. Osteoporos Int.

2020;31:1025-1048.

3. Camacho PM, et al. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(suppl

1):1-46

4. Lewiecki EM, et al. J Clin Densitom.

2016;19:127-140

5. Zhang J, et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:858-864

6. Adams AL, et al. J Bone Miner Res.

2018;33:1291-1301.

This transcript is provided for your convenience and is qualified by the full video in which the spoken content appears. Please review the full video along with the transcript.

Welcome to this video on a review of recently updated postmenopausal osteoporosis guidelines.

I am Dr. Steven Petak.

This disease awareness program is presented on Amgen’s behalf, and has been reviewed consistent with Amgen’s internal review policies

Here are my disclosures

I am also member of the Amgen and Alexion speaker bureaus.

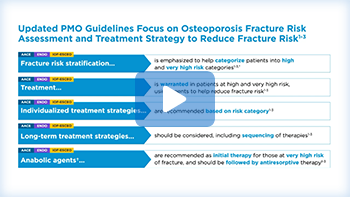

Over the past two years, several societies have released updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for postmenopausal osteoporosis. This includes the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology, the International Osteoporosis Foundation and European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis, and the Endocrine Society.1-3

These updated guidelines include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.1-4

There are some common themes between the updated postmenopausal osteoporosis guidelines as they focus on fracture risk assessment and treatment strategies.1-3

Fracture risk stratification is emphasized, and categorizes patients into high risk, and a new, very-highrisk risk category. ENDO and IOF-ESCEO Guidelines include both a low risk category, and ENDO additionally includes a moderate risk category.1-3

Treatment is recommended in patients at high and very high risk, and is individualized based on a patient’s risk classification.1-3

Given the chronic nature of osteoporosis, long-term treatment strategies should be considered, including sequencing. Anabolic agents are recommended as initial therapy for patients at very high risk, and AACE guidelines also include injectable anti-resorptives as an initial therapy option in very high risk patients. All three guidelines state that anabolic therapy should be followed with subsequent antiresorptive therapy.1-3

AACE, ENDO, and IOF-ESCEO guidelines all contain recommendations for fracture risk assessment.1,2,5

AACE recommends that all postmenopausal women 50 years and older be evaluated.1

In addition to patient’s history and physical exam, this guideline recommends that the initial evaluation include a clinical fracture risk assessment with the FRAX™ or other fracture risk assessment tools.1

Bone mineral density testing should also be considered in women age 65 years old or greater, or based on the clinical fracture risk profile.1

When BMD is measured, an axial dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) should be used (such as lumbar spine and hip, or 1/3 radius site if indicated).1

The ENDO guidelines recommend all postmenopausal women be evaluated for osteoporosis risk.2

BMD testing should be performed at the lumbar spine and hip, along with a clinical fracture risk assessment with FRAX™. 2

IOF-ESCEO recommends that postmenopausal women who have risk factors for fracture be assessed using the country-specific FRAX™ assessment.5

In patients with intermediate risk, DXA BMD measurements should be included in the FRAX™ calculation.5

Other measurements such as trabecular bone score may also be used in addition to BMD and FRAX™. 5

IOF-ESCEO guidelines further recommend that a vertebral fracture assessment should be considered if the patient has a history of height loss of greater than or equal to 4 cm, kyphosis, or current or recent long-term glucocorticoid therapy, or have a BMD T-score of –2.5 or worse.5

These guidelines provide some similar characterization of fracture risk, categorizing postmenopausal women as “high,” or “very high risk” fracture risk.1-3 The IOF-ESCEO and ENDO Guidelines also include a low fracture risk category, and ENDO additionally includes a moderate Risk category.2,3 We are going to focus on the high and very high risk categories.

Both the AACE and ENDO guidelines classify postmenopausal patients at high risk if they have a history of fracture, a T-score of –2.5 or worse, or an increased fracture risk using FRAX™ country-specific thresholds, shown here for the United States.1,2

Based on guidance from AACE, patients with a recent fracture within the past 12 months, with fractures while on osteoporosis therapy, multiple fractures, fractures while on drugs that cause skeletal harm (such as glucocorticoids), with a very low bone mineral density T-score (such as –3.0 or less), with a history of falls or have high risk for falls, or with a very high fracture probability by FRAX™ (for example, major osteoporosis fracture risk of more than 30%, or hip fracture risk of more than 4.5%) are considered to be at very high fracture risk.1

In the ENDO guidelines, patients are considered very high fracture risk if they have multiple spine fractures and a BMD T-score at the hip or spine of –2.5 or below.2

The IOF and ESCEO recommend that fracture risk is expressed as an absolute risk— probability of fracture over a 10-year interval. It depends on age, life expectancy, and current fracture risk, which is based on clinical risk factors.3

AACE guidelines provide new diagnostic criteria for osteoporosisin postmenopausal women.1

Osteoporosis can be diagnosed if there is a low-trauma (or a fragility) fracture in the absence of other metabolic bone disease, independent of the T-score.1

Individuals with low bone mass, such as a T-score between –1.0 and –2.5, but with a fragility fracture of the spine, hip, proximal humerus, pelvis, or distal forearm are also at a higher risk for future fractures. These individuals should be diagnosed with osteoporosis and pharmacologic therapy should be considered.1

Although traditionally osteoporosis has been diagnosed based on low bone mineral density in the absence of a fracture, the 2020 AACE guidelines state that patients with osteopenia and increased fracture risk using the FRAX™ country-specific thresholds should also be diagnosed with osteoporosis and should be treated.1

The indications for pharmacologic therapy are low T-score, increased fracture risk based on FRAX™, or fragility fracture. Once the diagnosis of osteoporosis is made, the diagnosis remains even if the patient’s T-score improves to better than −2.5 as a result of treatment.1

Guidelines also provide recommendations on who to treat based on history of fracture, FRAX™ fracture risk assessment tool, and T-score.1,2,5

AACE, ENDO, and IOF-ESCEO guidelines recommend that treatment should be provided in patients with a history of fracture. 1,2,5

AACE also includes the criteria of a T-score between –1.0 and –2.5 at the spine, femoral neck, total hip, or 1/3 radius.1

These three guidelines also recommend treatment in patients with increased fracture risk based on country-specific FRAX thresholds. 1,2,5

In the United States, these thresholds are: a FRAX™ 10-year probability of greater than or equal to 20% for major osteoporotic fractures, or greater than or equal to 3% for hip fractures.1,2

The AACE guidelines further specify a T-score between –1.0 and–2.5 in addition to increased fracture risk by FRAX™. 1

Both AACE and ENDO guidelines suggest that patients with a T-score of –2.5 or worse at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, or total hip should receive treatment.1,2

Presented on this slide is a general schema showing AACE recommendations for management of patients at high risk and very high risk.

For those patients who are considered ‘high’ fracture risk, AACE guidelines recommend these patients be started on oral antiresorptive agents.1

The treatment in these ‘high risk’ patients should be monitored by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry every 1 to 2 years until findings are stable.1

Clinical management depends on BMD and fracture risk category.1

For the patients that fall under the ‘very high’ risk category, AACE guidelines recommend initial treatment options that include anabolic therapy or an injectable antiresorptive.1

Reassessment recommendations are the same as the ‘high’ risk group, with a DXA test every 1 to 2 years as well.1

The guidelines state that an antiresorptive therapy should be used as sequential therapy after anabolic treatment.1

The Endocrine Society also has guidelines for treatment based on fracture risk stratification into ‘high risk’ and ‘very high risk’ categories.2

For those patients who are considered ‘high’ fracture risk, ENDO guidelines recommend initial treatment with antiresorptive agents, which can include bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators (or SERMs), menopausal hormone therapy, or calcitonin in selected patients. For example: in women who do not tolerate certain antiresorptive therapies, or in patients with high breast cancer risk, or in women with a hysterectomy and on estrogen-only therapy.2

Patients should be reassessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry every 1 to 3 years.2

For the patients under the ‘very high’ risk category, ENDO guidelines recommend that patients initiate with anabolic therapy for 1 to 2 years.2

In this ‘very high’ risk fracture group, the reassessment recommendations are the same as the ‘high’ risk group, a DXA test every 1 to 3 years.2

The guidelines recommend antiresorptive therapy be used after the completed course of anabolic therapy. This is to help maintain the bone mineral density gains with the initial therapy.2

For these two groups, the ‘high’ risk and ‘very high’ risk categories, the guideline recommends that the therapy continue, or if necessary, switch to another therapy.2

IOF-ESCEO also has an algorithm to risk stratify patients as low risk, high risk, or very high risk of fracture. Treatment recommendations are made based on this categorization.3

In all patients, risk-appropriate exercise and optimizing calcium and vitamin D status are recommended. Antiresorptive therapy is recommended for high risk patients. For very high risk patients, an anabolic agent followed by an inhibitor of bone resorption should be considered.3

In summary, assessment of fracture risk is important to identify individuals at high risk or very high risk for fractures.1-3

There is new criteria for the clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis, and it is based on patient risk factors in addition to bone mineral density.1-3

All three AACE, ENDO, and IOF-ESCEO updated guidelines offer treatment strategy recommendations for high risk and very high risk patients.1-3

Beyond these guidelines, clinicians should familiarize themselves with the tools and technologies available that can help identify patients at high risk that need treatment.

References:

1.Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2020 update. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(suppl1):1- 46.This transcript is provided for your convenience and is qualified by the full video in which the spoken content appears. Please review the full video along with the transcript.

Welcome to this video on recent trends in Osteoporosis.

I am Dr. Steven Petak.

This disease awareness program is presented on Amgen’s behalf, and has been reviewed consistent with Amgen’s internal review policies.

Here are my disclosures

I am a member of the Amgen and Alexion speaker bureaus

The incidence of osteoporosis in the United States is projected to increase over the next decade.1

Based on a US Census population, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimated that approximately 10 million adults in the US who are at least 50 years old had osteoporosis in 2010.1

This is based on a bone mineral density T-score of –2.5 or worse at either the femoral neck or lumbar spine.1

The report projected that the incidence of osteoporosis in this population will increase by 3.4 million in 2030, for an estimated 32% increase.1

The annual number of fractures in women at least 65 years old in the US is also projected to increase in the next two decades.2

In this study, a forecasting model was developed to project the annual incidence of osteoporotic fractures among US women at least 65 years old from 2018 to 2040.2

According to the projected model, the annual number of fractures is expected to increase by 68% by 2040 due to the aging and growing population.2

Despite the projected increase in incidence of osteoporosis that was presented in the previous slide, the rates of osteoporosis diagnosis and the rates of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (or DXA) testing declined between 2009 and 2014.3

This is based on a Medicare fee-for-service health claims database that includes women with at least one annual DXA scan.3

The rate of osteoporosis diagnosis was slightly less than 18% in 2009 among women 65 years old or greater.3

This rate decreased to 14.8% in 2014.3

This pattern of decrease was also seen with DXA testing, which was 13.2% in 2008 and decreased to 11.3% in 2014.3

There was a decline in fracture rates between 2007 and 2013.4

Specifically, among women 65 and older, the fracture rate dropped from 27.5 fractures for every 1,000 person-years, down to about 22.1. This represents a significant decrease of 3.4% per year.4

However, in more recent years, the fracture rate has reversed course and has been climbing up again.4

The data points shown in blue on this graph show a relative plateau since 2013, then an increase in fracture rate among women over the age of 65 in 2017.4

Many factors may have played a role in contributing to the increasing fracture rates.1,5

Since 2007, Medicare reimbursement for bone density screening was cut far below the actual cost of performing a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan. As a result, these services were less likely to be offered by physicians in solo practices, and practices with access to fewer than three DXA scanners.5

With the increasing number of fractures over recent years, it is important to recognize that osteoporosis-related fractures can have a negative impact on the patient and can be associated with disability and loss of independence.4

These fractures may prevent a person from caring for him or herself and may require admission to a nursing home or a long-term care facility.6

Costs due to fracture can create a heavy financial burden for the patient and caregivers.7-10

The patient may not be able to do some of the regular activities of daily living because of the fracture.6,11,12

Patients may worry about falls, the possibility of future fractures, and the potential need for nursing home care.8,13

And finally, complications such as chronic pain may occur.11,14

Once a patient experiences a fracture, the risk of having a subsequent fracture increases. This relationship holds true across different sites of initial fracture, including hip, clinical vertebral, upper limb, and lower limb.15

This study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association followed a cohort of ambulatory patients over a 16-year period. These patients lived in the community and not in nursing homes.15

Among elderly women who had a prior fracture, researchers found that the risk of an initial fracture increased with age.15

In addition, the risk for a subsequent fracture went up by 1.6 to 2.4 times.15

In fact, the risk of a subsequent fracture amongst women aged 60–69 years old who had a prior fracture (36%), was higher than the risk of an initial fracture among women aged 70–79 years old (27%).15

The same goes with those in the 70–79 year old group who had a prior fracture. Their risk for a subsequent fracture (63%) was higher than the risk of an initial fracture in those who were 80 years or older (50%).15

This data underscores the fact that the increased risk of a subsequent fracture persists for up to 10 years depending upon age and sex, and independent of initial fracture type.15

When examining the period following an osteoporosis-related fracture, it is evident that the highest risk of a re-fracture is within the first year after the initial fracture.16

This can be illustrated using data from a population-based study of over 4,100 postmenopausal women.16

In this study, fractures included hip fractures, major fractures (including clinical vertebral, forearm, and humerus), and minor fractures (all others), as classified by the World Health Organization.16

The relative risk of a subsequent fracture is 5 times greater in the first year after a fracture compared with the risk of a first fracture. One of every four subsequent fractures happen within the first year after the initial fracture. This further supports early action in prevention of a subsequent fracture.

In summary, osteoporosis-related fractures are common, and the rate has increased, but the rate of diagnosis of osteoporosis has decreased.1-3

The consequences of fractures are significant and can lead to disability and loss of independence, and even more than that, once a person has a fracture, they are more likely to have another fracture. 8,11,15,17

Clinicians should familiarize themselves with the most recent osteoporosis clinical guidelines that provide information that helps to identify and treat patients with osteoporosis.

References:

1. Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent

prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass

in the United States based on bone mineral density

at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J

Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520-2526.

2. Lewiecki EM, Ortendahl JD, Vanderpuye-Orgle J, et

al. Healthcare policy changes in osteoporosis

can improve outcomes and reduce costs in the United

States. JBMR Plus. 2019;3(9):e10192.

3. Lewiecki EM, Adler R, Curtis J, et al. Hip

fractures and declining DXA testing: at a breaking

point?

Presented at: American Society for Bone and Mineral

Research Annual Meeting. September 16-

19, 2016;Atlanta, GA. Abstract 1077.

4. Lewiecki EM, Chastek B, Sundquist K, et al.

Osteoporotic fracture trends in a population of US

managed care enrollees from 2007 to 2017. Osteoporos

Int. 2020;31(7):1299-1304

5. Hayes BL, Curtis JR, Laster A, et al.

Osteoporosis care in the United States after

declines in

reimbursements for DXA. J Clin Densitom.

2010;13(4):352-360.

6.Bentler SE, Liu L, Obrizan M, et al. The aftermath

of hip fracture: discharge placement,

functional status change, and mortality. Am J

Epidemiol. 2009;170(10):1290-1299.

7.Tajeu GS, Delzell E, Smith W, et al. Death,

debility, and destitution following hip fracture. J

Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(3):346-353.

8.National Osteoporosis Society. Life with

Osteoporosis. October 2014.https://www.laterlifetr

aining.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/NOS-Public-Report-V2.2-Small-file-size.pdf.

Accessed

February 4, 2021.

9.Tarride J-E, Hopkins RB, Leslie WD, et al. The

burden of illness of osteoporosis in Canada.

Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(11):2591-2600.

10.Kaffashian S, Raina P, Oremus M, et al. The

burden of osteoporotic fractures beyond acute care:

the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos).

Age Ageing. 2011;40(5):602-607.

11. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al.

Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of

osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381.

12.Fischer S, Kapinos KA, Mulcahy A, Pinto L, Hayden

O, Barron R. Estimating the long-term

functional burden of osteoporosis-related fractures.

Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(10):2843-2851.

13. Vass CD, Sahota O, Angelova T. Fear of falling

after fragility fracture–a prevalence study. Age

Ageing. 2014;43:i29.

14.Inacio MCS, Weiss JM, Miric A, Hunt JJ, Zohman

GL, Paxton EW. A community-based hip fracture

registry: population, methods, and outcomes. Perm J.

2015;19(3):29-36.

15.Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA. Risk of

subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture

in men and women. JAMA. 2007;297(4):387-394.

16.van Geel TACM, van Helden S, Geusens PP, Winkens

B, Dinant G-J. Clinical subsequent fractures

cluster in time after first fractures. Ann Rheum

Dis. 2009;68(1):99-102.

17.Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American

Association of Clinical

Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology

clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis

and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2020

update. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(suppl1):1-

46.

This transcript is provided for your convenience and is qualified by the full video in which the spoken content appears. Please review the full video along with the transcript.

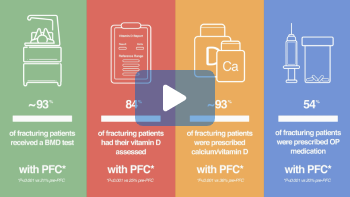

Once you experience a fracture due to osteoporosis, the risk of having another fracture goes up. A first fracture represents an opportunity to intervene with appropriate treatment to reduce the risk of a future fracture. Post-fracture care, or PFC, is a collaborative approach that helps patients who have experienced a fracture avoid subsequent fractures.

PFC involves a team of specialists, primary care and ER physicians, nurses, and other health care staff, who all work together to decrease the risk of the patient fracturing again.

PFC programs are important because they improve patient follow-up, testing, and treatment for osteoporosis.

The percentages of patients who received follow-up, testing, and treatment were significantly higher after PFC than before PFC.

Primary care practitioners have a key role in PFC programs.

When receiving patients from PFC, primary care practitioners should maintain appropriate communication with patients, other physicians, and PFC team members maintain the patient’s treatment plan continue to conduct bone health assessments and continue to evaluate risk factors for fracture.